Mark Hubbard Remembered

1/14/2019

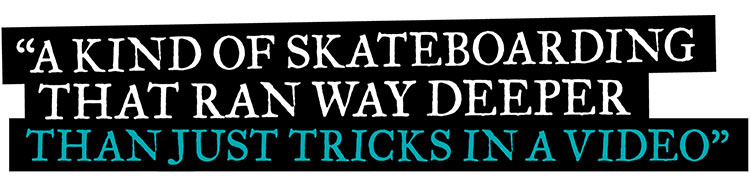

Words by Wez Lundry

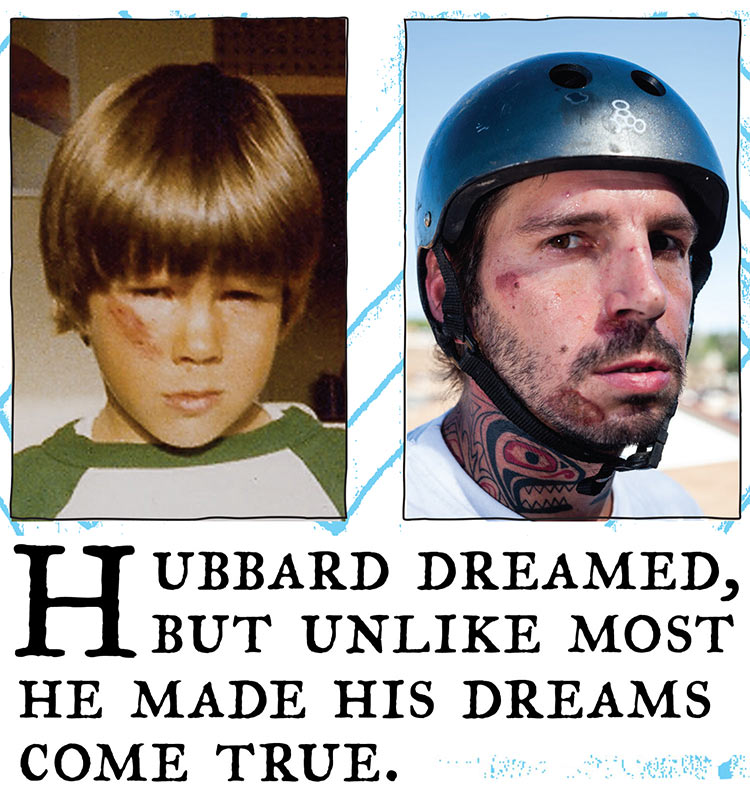

WHEN MARK WAS YOUNG he would tell us his dreams. His ideas were so cool but somehow unimaginable. He spent days drawing skateparks with M.C. Escher-inspired architecture, interconnected full pipes and deep bowls, portals into different dimensions. For those of us who came of age just after the first skatepark boom and who grew up on driveway quarterpipes, backyard halfpipes, curbs, ditches, pools and pipes, the notion that cities would one day pour gigantic concrete playgrounds for us to ride for free was unfathomable. When Hubbard would say stuff, like, “I want to pave the world,” we were psyched but thought it would remain a backyard and DIY thing. Mark made dreams happen, and I’m reminded of that every time I fly into Sea-Tac airport and see the River City Skatepark in Southpark from the plane, which looks like a skateboarding Stonehenge or dimensional portal. Some of his designs are simply cosmic-—I have no doubt that the claymation segment of the movie Skateboard Madness was an inspiration, with concrete waves breaking over and over again. Hubbard wanted to make this a reality. He talked about ribbons of pump-able concrete as a means to commute, or paths through cities littered with micro skate spots, which is another idea that cities are starting to embrace.

At ease in any environment, Mark not only ripped backyard bowls but found inspiration in them for his park designs

At ease in any environment, Mark not only ripped backyard bowls but found inspiration in them for his park designsOn June 8, 2018, we lost one of the most influential people to ever step foot on a skateboard—Roger Mark Hubbard, also known as Monk, Mank, Mink, Marty or about half a dozen other names. Monk left behind a loving family, a world full of close friends and thousands of skate rats whose lives he touched. It’s been six months and I still can’t believe he’s gone. I met Mark when he was about 14. He was hardscrabble—messy and dirty and unconcerned with appearances, an aesthetic he maintained. In the ’80s he bought Z-Blanks, heavy blank slabs of laminated wood which you could cut a shape from, and simply drilled truck holes and rode them as is. He was 100-percent skate rat, and like most of us, skating was all he cared about.

DIY... do or die. Building shit wasn't just a job for Monk, it was a lifestyle. Spots over profits

DIY... do or die. Building shit wasn't just a job for Monk, it was a lifestyle. Spots over profitsHubbard swore from an early age that he would give us somewhere to skate, that he would create jobs for skaters, build more parks and he made that happen. Grindline has employed more than 225 people—some lifers, some for one or two projects, some broke away and started their own companies. But Mark’s most significant contribution is the fact that there are hundreds of skaters throughout the world who can now build cement skateparks: a corps of engineers for the skate army.

Not taking no for an answer, Mark turned the Schmitz Park bust into the West Seattle bowl, and then commenced ripping it upon completion

Not taking no for an answer, Mark turned the Schmitz Park bust into the West Seattle bowl, and then commenced ripping it upon completionIn Seattle in the ’80s, we always built stuff to ride ourselves, as did most people back then. The surviving skateparks from the 1970s—Del Mar, Upland, Kona, Ocean City—were relics of a bygone era. Skating had moved into backyards and wood was the medium. Concrete skateparks seemed to be in the rear-view mirror forever. Little did we know a revolution was afoot and the second wave of parks was on the horizon. But this time instead of memberships, pads and paying for sessions, parks would be free and the best ones would be outside of California and Florida.

Hubbard was a perpetual fountain of creativity—music, drawings, art, imagining. Grindline the Band was another outlet for relating life on the board

Hubbard was a perpetual fountain of creativity—music, drawings, art, imagining. Grindline the Band was another outlet for relating life on the boardUnder the Burnside Bridge in Portland, Oregon, in 1990 was ground zero. Mark teamed up with Mark “Red” Scott and a crew of guys who brought bags of concrete under a bridge inhabited by junkies and prostitutes. In 1990 skateboarders were not afforded space or thought of highly. In Portland, however, we were at least better than the drug addicts and hookers. Maybe not much better, but we were allowed to continue building while the seedier elements faded into other dark corners. It was gnarly—the first bowl was about six feet deep with three cinder blocks of vert and maybe 12 feet in diameter—but the momentum spread. Mark was a ringleader for the Schmitz Park Bridge project in Seattle in late 1991. That got busted but it led to the West Seattle bowl.

Hubbard was a Burnside local and contributor from the earliest days. Here he pulls in a frontside pivot on the punk wall

Hubbard was a Burnside local and contributor from the earliest days. Here he pulls in a frontside pivot on the punk wallMark and the crew knew the basics—digging a hole, shaping it, tying rebar—but the rest was pretty rough around the edges. West Seattle is rugged, but it was all we had to skate in Seattle for years, thanks to Mark. When Hubbard found out the guy who was renting the place had split, he bought the house and saved the bowl. Mark had already been hopping on trains, frequently with the Q-Man, to ride terrain in other places. He had a truck with a camper and he constantly took research trips—Stone Edge in Florida, the Turf in Milwaukee, backyard pools across the country. He wanted to create something permanent and the next piece of the puzzle was honing his skills.

Road life—Mark loved skating as much as life itself, and it took him all over the world. Hell Ride in Quito, Ecuador, 2018

Road life—Mark loved skating as much as life itself, and it took him all over the world. Hell Ride in Quito, Ecuador, 2018In April of 1992, he got a job with Rhodes Masonry installing pool coping. This was a step towards learning how to smooth things out. Washington, Oregon and Colorado began leading the way with the opening of free, outdoor public skateparks, but a lot of the early ones sucked. Built by non-skaters and contracted to the lowest bidder, they didn’t flow, the coping was fucked, they were kinky, lumpy and rough, thus, the Certified Piece of Suck mantle was born. Hubbard saw the way out. Lincoln City, Oregon, contacted Red in 1998 because of Burnside. They knew they wanted the gnarliest and the best. Burnside had become a skate Mecca. They hired Mark and Red and some others as parks-and-rec employees in June of 1999, and the park opened in 2000. A sleepy coastal Oregon town became another must-hit skate destination. Newberg, Oregon, soon followed.

Hubbard’s approach was always on edge

Hubbard’s approach was always on edgeMark and Mike Swim got jobs at Johnson Western building vertical retaining walls and learning shotcrete. Mark and Mike, along with Rob Owen, Jay Iding and Dave “Shaggy” Palmer, built the Bainbridge Island park in 2001 and it was lined with pool coping. They built Sumner that same year. In April of 2002, Mark founded Grindline and built the Scott Stamnes Memorial Park on Orcas Island. The bar was raised yet again. The city had sought out Hubbard because his reputation had grown, because he was tight with Scott and because it felt right. Shitty parks were still being built, but they had lost their luster. Grindline’s parks, and a few others, got coverage, people made trips to skate them and the kids started ripping. And Grindline was hiring.

Mark and Jenny with their kids Kaya, Leona, and Odin. Thanks to everyone who helped out with his GoFundMe

Mark and Jenny with their kids Kaya, Leona, and Odin. Thanks to everyone who helped out with his GoFundMeWhen good parks started popping up, we predicted that there would be a younger generation of ATV pros coming up from the Northwest and that’s exactly what happened. And when you think about this, along with what is perhaps the most significant revolution in skateboarding, the DIY revolution, the possibilities are endless. All of the guys who work at Grindline put in time building DIY spots as well—Burnside, Marginal Way, FDR, WSVT, Channel Street and so many others. In places where there are no parks, skaters create one. Some are rejected but others are recognized for what they are: revolutionary free areas where the people who ride them have an interest in their maintenance and reputation.

Mark was always go-for-broke, make-it-or-slam. Indy air on a Vancouver, BC, indoor vert ramp

Mark was always go-for-broke, make-it-or-slam. Indy air on a Vancouver, BC, indoor vert ramp Grindline’s motto is “building parks and burning bridges” and they live it. They tweak designs if it feels right or if it will open up a line. They will put in extra time or go over budget. They want it to be better because they want to skate it, too, unlike corporate non-skater builders. Small towns and less bureaucracy enable them to innovate: building cradles, fullpipes, installing exposed aggregate coping, crafting portals.

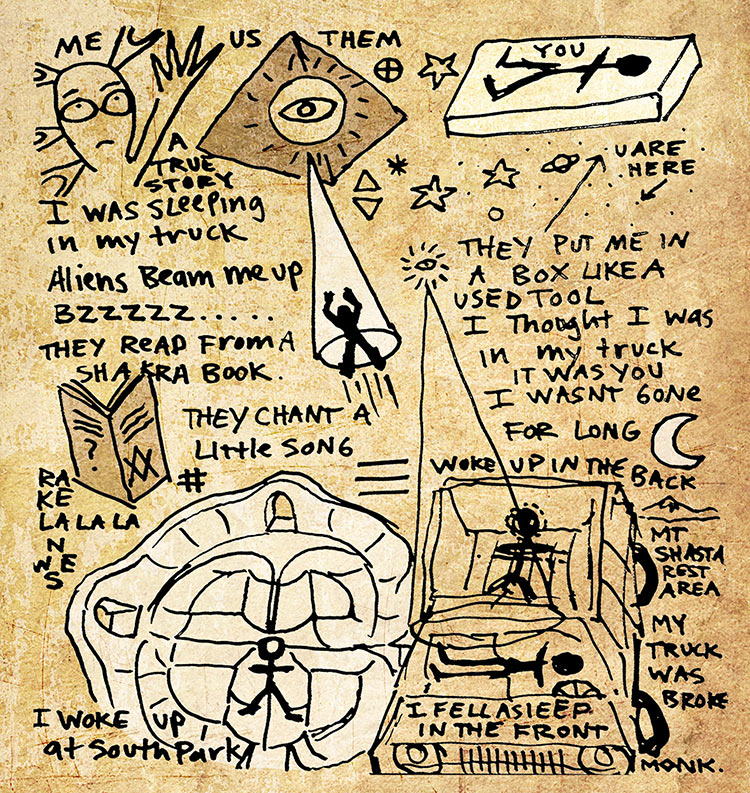

Sacred scrawls

Sacred scrawlsMonk’s contribution to this world was spiritual as well. He talked of cosmic consciousness and interconnectedness, which was influenced by his Native American ancestry. He was made an honorary member of the Pine Ridge Tribe while building a park there. It may sound paradoxical to think that someone who wanted to pave the world was also in touch with the natural environment in such a deep way, but if you ever met Mark you would understand how this could be true. He also painted, sculpted and made things, always working on something new. He was a musician. He taught himself how to play and would record himself jamming with a drum machine. There’s a Hubbard rap tape out there somewhere. And eventually that coalesced into Grindline the Band, which played benefits and did the Skate Rock tours. Mark never stopped hitting the road. He gave so much of himself to skateboarding and skateboarding brought him all over the world in return.

Mike Ranquet's ramp was big for the time, 10' tranny, 2' of vert, and it's where Hubbard started blasting. Photo: Kanights

Mike Ranquet's ramp was big for the time, 10' tranny, 2' of vert, and it's where Hubbard started blasting. Photo: KanightsI texted Mark the day before he died but didn’t hear back. I posted a photo of him the next day, then heard the news. Cosmic connectedness? I reached out to my friends and some reported the same type of thing—Mark in a dream, for example. I headed to Seattle shortly thereafter and worked with Shag and others to start a GoFundMe and to plan a celebration of Mark’s life. Hundreds gathered at Delridge Skatepark—Grindline-built and in Mark’s old neighborhood—to share embraces and stories of Mark’s days and to ponder the future without him physically. But we also acknowledged that he will always be with us in the permanence of the places he built and his influence that so drastically changed the way we think about the nature of skating. But perhaps more importantly we all took some runs, did some grinds, laughed, cheered, slammed, yelled, had a beer and had a good time. Monk would have wanted it that way.

Rest easy, Mark, and thank you.

Words By Sam Hitz

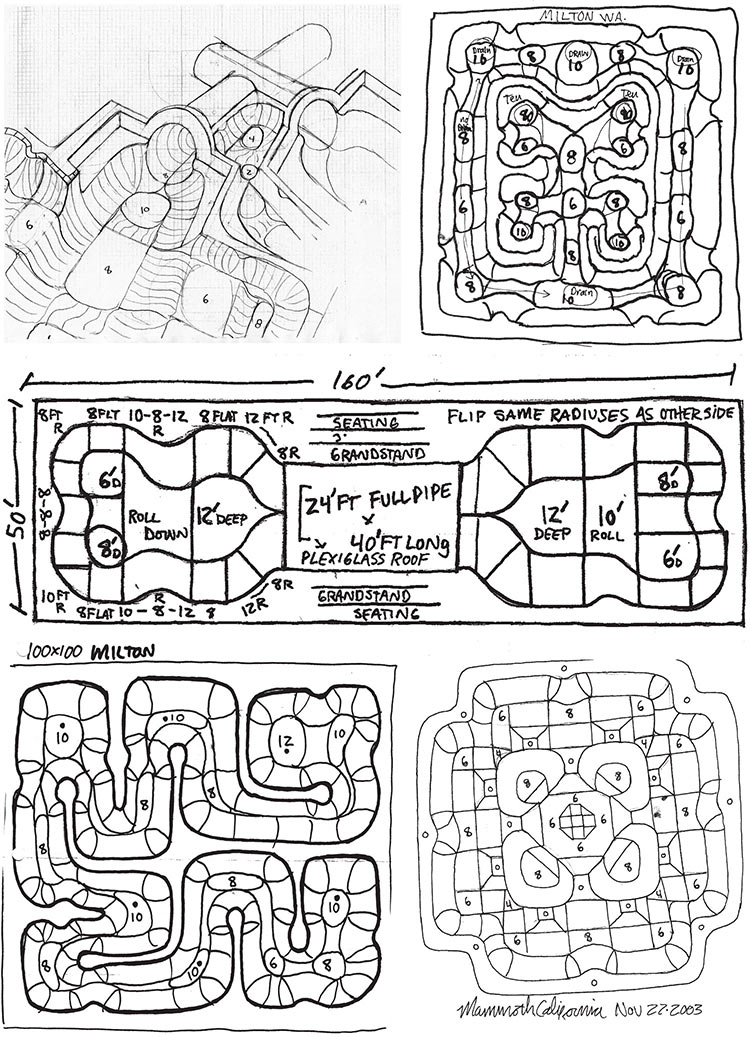

HUBBARD MADE PLENTY of pilgrimages to The Turf, my home skatepark, starting in about ’89. He showed up by rail the first time and made camp in the brush about 100 feet behind the park. Me and a couple of the other kids rolled up on him and were just in awe. He looked like Mad Max and was tending to a little campfire. He said he was trying to get a job at the George Webb diner across the street and he asked if we could raid our mom’s cabinets for some canned soup or beans. We totally obliged and showed up the next day with an assorted haul of goods. The scenario was like a Norman Rockwell painting—here’s these kids all padded up, ready to skate, handing canned goods over a small campfire to a train-hopping renegade skateboarder in the woods. Pure fucking Americana!

The sessions that week were gonzo too. Hubbard skated the hardest and least traveled ways—always starting on the side of the capsule with the decks and rolling into the escalators that reached 13 feet—or jumping over the channel of the Keyhole from a stand-still Texas plant boost. Throughout those years he showed up with the likes of Scott Smiley, the OG West Seattle crew and of course Redneck (which is a whole story in itself). So many heads traveled to The Turf during its short resurrection but Hubbard’s appearances enlightened me to the knowledge that a skateboarder can truly have—worldly knowledge that ran way deeper than just just tricks in a video. He opened my eyes to the fact that I was part of something way bigger than just my local scene and that I had to get out there and find it.

The sessions that week were gonzo too. Hubbard skated the hardest and least traveled ways—always starting on the side of the capsule with the decks and rolling into the escalators that reached 13 feet—or jumping over the channel of the Keyhole from a stand-still Texas plant boost. Throughout those years he showed up with the likes of Scott Smiley, the OG West Seattle crew and of course Redneck (which is a whole story in itself). So many heads traveled to The Turf during its short resurrection but Hubbard’s appearances enlightened me to the knowledge that a skateboarder can truly have—worldly knowledge that ran way deeper than just just tricks in a video. He opened my eyes to the fact that I was part of something way bigger than just my local scene and that I had to get out there and find it.  Mark's drawings

Mark's drawings Scott and Mark

Scott and MarkWords By Scott Smiley

WHEN MARK HUBBARD first came into my life we were eight years old and I couldn’t stand him. He used to follow me home from school and beat me up. Mostly because in 3rd grade I was the toughest in line after him and he wanted the challenge. He also just wanted me to be his friend, which I didn’t want yet so he beat it into me. I eventually gave in and came around. His dad Roger was our little league baseball coach. He used to yell at us for throwing rocks at each other in the outfield instead of paying attention to the game. We both had skateboards since we were five or six and it didn’t take us long to scrap team sports. Mark had a craving or calling to be on the road, mostly in search of empty pools, new spots and to find other crazy, passionate and energetic characters like himself. We made it from Seattle to Upland skatepark in CA together before we were even old enough to drive, with fake IDs at the ready so we could sign the waiver to skate the park. In my eyes, he is the original king of the road. In Milwaukee at The Turf I gave him a haircut with a receding hairline to make him look like an old man so he could buy beer for us. He didn’t even like drinking with us yet but he was still willing. He always had a hipper from slamming so he would limp into the local mom ’n’ pop with his head down and growl, “I’m 38 years old, damn it.” He must have tried 15 times. It worked twice. As the cut grew out on top we told him he looked like a monk. Whenever he’d get busted by the cops for trespassing to skate he’d tell them his name was Mink Mank Monk.

In high school he would draw endless skatepark configurations and tell me, “Someday, Morty,” and I’d say “Yeah right, Marty.” Boy was I wrong. Everything he put his mind to came to fruition. He made it all over the world skating, from backyards to overseas pro circuits. It was will over skill and it was beautifully ugly. Mark has forever changed the face of the world for the better. He would venture to say he changed the universe and if I only had one more chance I would never doubt him again. Being Mark’s best friend is my honor and having him in our lives for as long as we did is our blessing. But Mark was everybody’s best friend; he treated everyone the same. If you were lucky enough to be tight with him then I know you pissed him off at times. So you also know that would only last a few moments because to say he was forgiving is an understatement. We all owe Monk a great deal and we owe it to him to keep it going in his style—rip ride never die, Marty. I will be borrowing from his existence from here on out to make myself a better person. I hope you do the same. I love you, Marty.

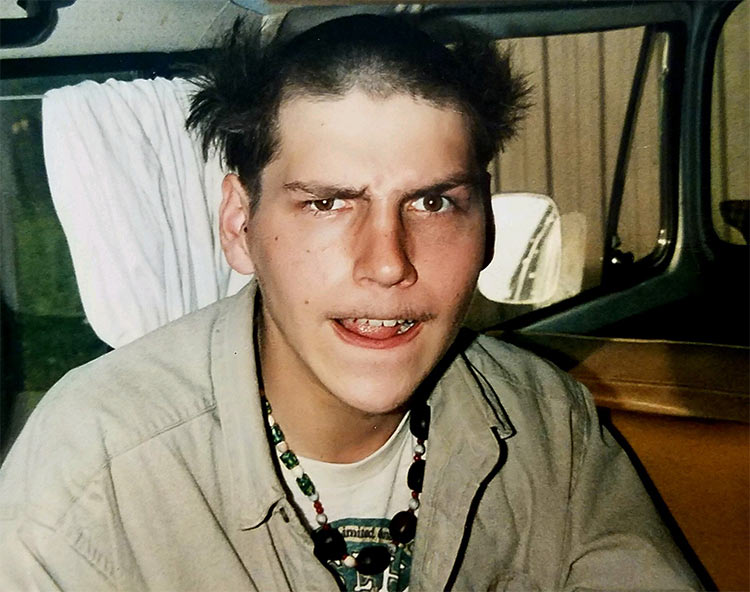

In high school he would draw endless skatepark configurations and tell me, “Someday, Morty,” and I’d say “Yeah right, Marty.” Boy was I wrong. Everything he put his mind to came to fruition. He made it all over the world skating, from backyards to overseas pro circuits. It was will over skill and it was beautifully ugly. Mark has forever changed the face of the world for the better. He would venture to say he changed the universe and if I only had one more chance I would never doubt him again. Being Mark’s best friend is my honor and having him in our lives for as long as we did is our blessing. But Mark was everybody’s best friend; he treated everyone the same. If you were lucky enough to be tight with him then I know you pissed him off at times. So you also know that would only last a few moments because to say he was forgiving is an understatement. We all owe Monk a great deal and we owe it to him to keep it going in his style—rip ride never die, Marty. I will be borrowing from his existence from here on out to make myself a better person. I hope you do the same. I love you, Marty. Too young to buy beer, Mark shaved his head to look older but ended up looking like a monk. The moniker stuck. This is the "grow out" phase

Too young to buy beer, Mark shaved his head to look older but ended up looking like a monk. The moniker stuck. This is the "grow out" phase Coping crunch down under

Coping crunch down under

Words By Jake Phelps

YOU CAN TELL a lot about a person by the amount of miles you do with them. Mark Hubbard and I did a lot of miles together. He always made me laugh and always listened. Away from a skateboarding standpoint, he was like the Leonardo Da Vinci of this time. He would design it, sketch it out in a book and tell you about it exactly. Where do you fucking go to now that he’s gone? He told me one time, and I think about it more than ever, that your body is just a vessel, the energy in the love that you emit from your body goes on forever. Just as there’s only a certain amount of water on Earth, there’s only a certain amount of love in the world. Marty had more love than any man I’ve ever met. My best friend, part of me, died June 8, 2018.

For more testimonials and photos of Mark, click here.

To keep his music alive and rocking, check out Grindline the Band.

-

4/18/2022

P-Stone Cup 2022 Photos

The P-Stone Cup is a bonafide Bay Area spectacle, a who's who of the rawest transition talent from across the globe. Joe Brook reports on every rip and rare sighting from one of skateboarding's best days. -

1/17/2022

Grindland Extras: "Red and Monk Hit the Turf" Cartoon by The Larb

A hilarious Hellride from Seattle to Milwaukee gets the Larb animation treatment. Believe it! -

1/14/2022

“Grindland – Red, Monk and the Birth of DIY” Full Movie

From the early days of Burnside to 2019’s Rip Ride Rally, this film explores the friendship, struggle, triumph and tragedy of DIY pioneers Mark Scott and Mark Hubbard –– true iconoclasts hellbent on building the skateparks of their dreams. Watch this with your friends. -

11/02/2020

Burnside 4 Life: 30 Years Under The Bridge Video

Three decades of destruction smashed into six minutes. Big ups to everyone who’s chipped in or got broke off under the bridge. Fuel the stoke and build your own. -

11/02/2020

Burnside 4 Life: 30 Years Under The Bridge Article

Burnside’s birthday marks 30 years of spills and thrills at the first renegade DIY. Read how the founders took it from vagrant hideaway to Northwest proving ground in our December ‘20 mag piece.